The Paul K. Feyerabend Foundation – in line with Paul’s work?

I usually do not take part in discussions about Paul’s work, not even in this year of his centennial anniversary, because I have little to say professionally about the topic. My relationship with Paul was personal, and I am very biased about him. But I am now pleased to offer a reflection about the connection between Paul’s work and the aims of the Foundation established to his name.

The Foundation is not dedicated to history or philosophy of science but to support concrete initiatives and exemplary work that improve the lives of unprivileged communities. Would Paul be happy about this goal? Considering this question today, thirty years after his ‘departure from the planet’, I am reminded of how he stressed that abstract thinking and ideas are capable of diminishing and even suffocating the ‘abundance of life’ around us, how he recommended staying close to the experience, knowledge and needs of real people. Rather than dispensing arrogant descriptions of ‘reality’ he preferred telling stories, describing complexities, asking questions, revealing the unexpected humor in the details. He was sincerely kind with the individuals he knew. When asked, he would provide practical help to make their lives a bit more satisfactory or less difficult. But he never bestowed ‘solutions’. Would the idea of a humanitarian foundation displease him?

In the occasion of Paul’s centennial anniversary, I realized that two themes from his work appear particularly relevant for the Foundation dedicated to his name. The first theme is the one of the ‘abundance of life’ that surrounds us, which many tend to reduce to one or the other, more-or-less drab, sense of ‘reality’. To counteract this ‘reduction of abundance’ Paul suggested embracing pluralism and diversity. He promoted a ‘proliferation’ of methods, ideas, theories, points of view and traditions and favored relations of mutual curiosity, respect and dialogue. A simplistic consequence that I draw from this is that–— whatever we believe to be real and important in life— be it the laws of physics; being ‘God’s chosen people’; amassing personal wealth; or relating with one other in ways that are peaceful and mutually enriching— that is not the only one possible, valid and ‘true’ understanding. If we accept that there are many and diverse beliefs about what is real and relevant in the world, that those sustain many and diverse ways of living, and that those make sense, and make life satisfactory for different people… we may feel at first quite unsettled. Ultimately, however, we may perceive a sense of liberation and openness.

Yes, all that exists— which Paul called ‘Being’— does not equally respond to and sustain all beliefs, interpretations, narratives and ways of living… but ‘Being’ does sustain and respond to many approaches, rather than one only. We all know people who have weird ideas (i.e., ideas that are ‘very different from ours’), behave strangely, and live in a world ‘of their own’. Yet, they manage to go on with their lives. Personally, I have met poor and illiterate individuals who were more effective at what they did, and kinder to others, than highly educated individuals with prestigious jobs and salaries. I am inclined to say that these peoples live in different ‘worlds’… but could anyone say that one is more real or more important than the other? More fundamentally, reading Paul’s work I started considering that different approaches to ‘Being’— for instance diverse scientific approaches or diverse narratives and worldviews— do affect ‘Being’ itself, and certainly affect our lives. Diverse approaches can be more or less useful in reaching the goals set by those who practice them or articulate their narratives. But they also contribute to make many of us, at the receiving end, miserable or satisfied, benevolent or criminal.

It seems to me that two consequences derive from these understandings. First, if a diversity of approaches to ‘Being’ is possible and effective in sustaining livelihoods and lives, we should ask ourselves why we should accept the views of those who emphatically tell us they know ‘the truth’ (e.g., scientists, priests, politicians, or development experts…). It is certainly wise and appropriate to take their views into account, but it is also important to live in “a world that is appropriate, relevant and meaningful for us” or— in Paul’s words— “a world that makes sense to us”. Further, this would not need to apply only to ourselves and our own worldviews. It seems to me that Paul encourages a sincere appreciation and respect for all ways of living that make life possible and sustainable for communities in a variety of circumstances. This is nothing else than a sincere and non-condescending appreciation of diverse cultures and traditions, offering diverse ways of understanding ‘reality’, ‘truth’, ‘nature’, ‘meaning’, ‘wellbeing’, ‘progress’, and ‘development’. [As first affirmed by Aimé Césaire, the violent erasure of cultures integral to colonialism has enormously impoverished the world. And that ongoing erasure is still primary to our globalized society, including in deeply paradoxical ways, from the military imposition of Western democracies to the cultural imposition of identity politics.]

Not all views and opinions count equally or have the same consequences. Some, for instance, thrive on weapons and wars, misery and divisions, racism and theft, the destruction of nature and the misery of others. Paul loved the Dada movement, which rebelled against the stupidity and callousness of the powers that provoked and maintained the First World War, causing millions of deaths and immense accompanying misery. Very much in line with the Dada movement, Paul resented the pontification of those who try to convince and corral others in ways that are dogmatic, humorless and inflexible. But… if all views and ways of living are not equally appreciable, how can we distinguish between the views and actions that should be kept in check and those who merit support and flourishing?

This question offers an entry into the second theme that I would like to highlight in Paul’s work— which is only apparently in opposition to the first. This is the understanding (in Paul’s words) that “every culture is potentially all cultures” and that diverse cultural manifestations are grounded in a ‘shared human nature’ that links and connects us all. Paul discusses this in the context of relativism, to overcome the idea that ‘cultures’ are incommensurable systems, closed upon themselves and hardly able to interact and communicate. For what concerns me, however, that understanding resonates with my feelings of empathy towards others, what some refer to as ‘compassion’, or ‘feeling together with others who are suffering’.

If we remove the myriad of our individual preferences, frameworks, and understandings of the world, what inescapably remains is our ‘shared human nature’. We may have different hierarchies of values and different interpretations of personal behaviors and political events, but we all know what it means to be hungry, sick and cold, or to feel relaxed breathing fresh air in a quiet natural environment. Of course, we do not have a way to compare such feelings and say they are exactly “the same” for all of us, but we may assume they are at least similar. In other words, we may assume some closeness among us fellow humans as we all have a body, we all were born, we all grew up, we all grow old, we all suffer, we all have some sense of pleasure, we all hurt, we all heal, and we will all die. Within the vast confines of our personal freedom and differences, we may recognize a basic oneness among us all, and a feeling— not a rational thought but a feeling—that it is good to ease the lives of others, to be compassionate towards them, to be ‘with’ and not against them. In fact, for the most fortunate among us, this sense of oneness may even extend to the world of animals, plants, life in general, the entire universe.

This oneness with other humans, possibly even with nature in general, can be the cornerstone of a sense of morality. As I perceive it, it encourages us all to feel and be with others and, in essence, to respect life in humans and in the rest of nature. This hardly constitutes a discovery, as the principle is common to many religions, and even to secular mores… but it certainly opens up an avenue for comfort and peace of mind. It also opens up an avenue for consequent ‘proper’ political behavior, as the interests and worldview of a specific group or culture should not be allowed to impede and crush the livelihoods of others and the worldviews “that make sense for them”. The concept of ‘self-determination’ is the one that most concisely summarizes this understanding. Noticeably, self-determination is fully enshrined in the UN Charter and the International Court of Justice… although regularly disattended and neglected in practice.

The two themes I have mentioned— the abundance of life and the understanding that “every culture is potentially all cultures”— are dealt with by Paul in Farewell to Reason and Conquest of Abundance. Possibly, however, the easiest way to approach them is from his Autobiography, which recounts how these themes emerged in his life relatively late, as a by-product of having related with others— and clearly not because of abstract reasoning, rational arguments or trying to follow principles and ideas. He recounts how, for him, developing something close to a ‘moral character’ and an ethos was a byproduct of feeling close to other human beings, through personal connections, acceptance, companionship and love.

Based on the two themes and the attitude just mentioned, I do hope that the Paul K. Feyerabend Foundation is in line with Paul’s ethos. The Foundation was formally established under Swiss law in 2006. The co-founders were a group of colleagues and friends who remain good friends and colleagues many years later (not a small feat!) and are still on the Board. The establishment came after a gestation of years, as we tried different ways to help people less materially fortunate than us, but not less able to run their lives and gain their livelihoods in difficult circumstances. One of the most inspiring co-founders, most unfortunately, is no longer with us, but some younger colleagues did join later. From the beginning, we chose to deal with communities rather than individuals because we believed that communities are stronger in facing the power structures that maintain injustice in the world. And we rejected the idea of charity— which may be providing ‘help’ without any commitment to fundamental change in the giver or receiver alike. We tried, instead, to embrace solidarity— engaging the foundation with its beneficiaries to understand together, and try to eliminate, the causes of problems and injustice.

For eighteen years, the Feyerabend Foundation has done its best to assist unprivileged communities to figure out for themselves what they need and want and what they can do— via internal solidarity and in solidarity with others— to fight injustice, promote their own wellbeing and maintain cultural and biological diversity. The inspiring concepts for the Foundation are thus community, solidarity, diversity (e.g., cultural, biological), and justice. All of them can be seen in line with the two ‘themes’ I mentioned above. On the one hand, the Foundation supports the diversity and abundance that makes life worth living— by promoting self-determination in diverse landscapes, cultures, languages and worldviews. On the one other, it nourishes ‘solidarity’ and ‘justice’, by strengthening the sense of a ‘single human nature’ that links and connects us all.

Being against the grain of the mainstream— about ‘scientific method’ or the normalized attitudes of selfishness, political conformism and the acceptance of militarism— is another way for the ethos of the foundation to connect to the work of Paul. Personally, I like to recall his profound loathing of arrogance, racism and violence— from gratuitous personal aggrandizement to the state sponsored apartheid and genocidal behavior unfortunately rampant today. I recall his desire to stay close to the experience and needs of people, possibly contributing something positive, however small, but always in line with their own wishes and perspectives. I recall his sincere appreciation of what everyone can offer— each of us from a diverse perspective and experience of life. He often conveyed the feeling, with his behavior more than with words, that being free is fundamental to wellbeing. Yet, he also admired the Paul Robesons of this world, people dedicated to political and human solidarity, ready to play and create beauty but also to work hard for the sake of justice, for the wellbeing of all.

It is in resonance with all of the above that I find my own motivations to engage time, energy and resources to keep alive the Feyerabend Foundation, and I know that others in the Board of the Foundation have similar feelings. At the time of writing, nothing is more urgent than unmasking the pernicious racism and militarization of our societies aided and abetted by those politicians and media that keep conning us all, pursuing their own, particular interests at the expense of the interests and wellbeing of most others. Paul’s appreciation of history and abundance of life, his capacity to think ‘outside of the box’ and his gentle call to perceive our shared humanity are— it seems to me— needed today more than ever.

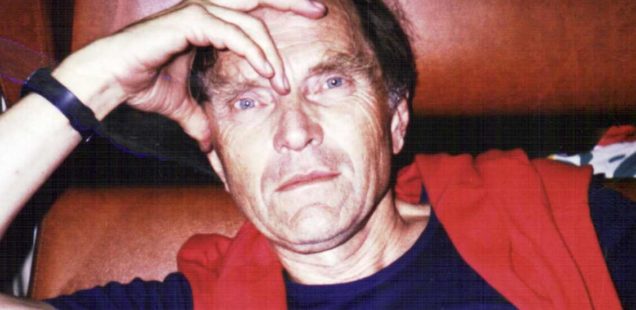

Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, September 2024